Martin Robson’s A History of the Royal Navy: The Napoleonic Wars is a valuable addition to the new history of the Royal Navy series published by I.B. Tauris in association with the National Museum of the Royal Navy. Robson’s contribution to this authoritative series is a concise yet comprehensive analysis of the role of the Royal Navy in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars from the declaration of war in 1793 to the bombardment of Algiers in 1816. However this is much more than simply a history of naval warfare, as Robson frames the actions of the navy and the war at sea in the wider socio-political and global economic context of the period.

In a brief but valuable introduction Robson clearly defines Britain’s war objectives, a critical point unaccountably overlooked by many naval histories. Britain’s peripheral position in relation to the European continental system is contrasted with the country’s central place in a global maritime empire encompassing the East and West Indies together with parts of North America. This empire was founded on maritime commerce and thus the Royal Navy played a central role in protecting Britain’s global maritime trade interests and ensuring that the country had the economic power to support and subsidise its continental allies. The navy became the means by which British war aims could be achieved through maritime conflict.

In a brief but valuable introduction Robson clearly defines Britain’s war objectives, a critical point unaccountably overlooked by many naval histories. Britain’s peripheral position in relation to the European continental system is contrasted with the country’s central place in a global maritime empire encompassing the East and West Indies together with parts of North America. This empire was founded on maritime commerce and thus the Royal Navy played a central role in protecting Britain’s global maritime trade interests and ensuring that the country had the economic power to support and subsidise its continental allies. The navy became the means by which British war aims could be achieved through maritime conflict.

Rather than presenting a strictly chronological account, Robson has employed both a chronological and geographical framework to order his narrative, with successive chapters focusing on events occurring in each of the main theatres of war; home waters, the Mediterranean, the Baltic, the East and West Indies, etc. This approach results in the account jumping backwards and forwards in time, but the text is sufficiently coherent to ensure that the reader never looses the thread of the narrative.

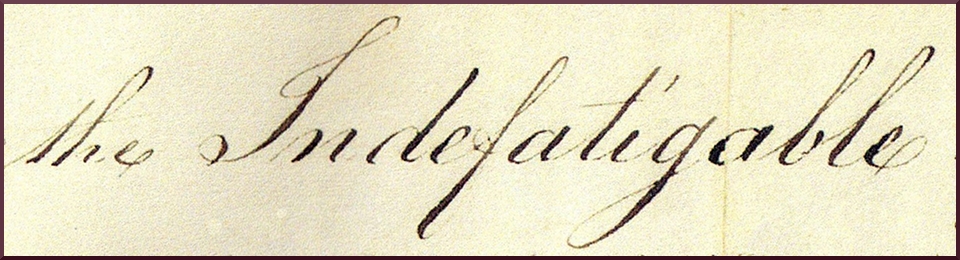

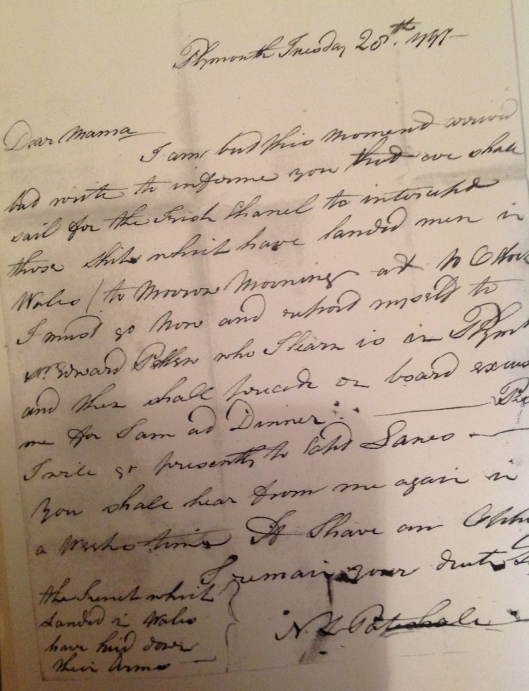

The historical account begins in home waters with Howe’s Channel fleet and the tactical role played both by the close blockade system and by Warren and Pellew’s detached frigate squadrons. Robson explores the strategic impact of the Glorious First of June and the battle of Camperdown before turning this attention to the Mediterranean, the Spanish declaration of war, the disastrous assault on Tenerife and the more successful Egyptian campaigns. In such a wide-ranging history individual events are necessarily summarised, however some, such as the siege of Acre, seem overly truncated. Moving on to the East and West Indies and the Cape, Robson focuses on how events in the main theatre of war in Europe influenced and affected campaigns overseas.

Inevitably, the figure of Nelson looms large over proceedings, indeed the book is prefaced by a stirring account of his final moments, however Robson does not shrink from acknowledging his failings in politics and diplomacy and he is always prepared to give Nelson’s fellow captains their due, e.g. Foley, who is credited with the initiative of advancing inshore of the French line at the battle at the Nile. Robson also presents a welcome reappraisal of Calder’s engagement prior to the battle of Trafalgar, and while acknowledging that Calder was criticized for not delivering a decisive “Nelsonic style” victory, he also argues that Calder achieved his main strategic and tactical objective by preventing Villeneuve’s fleet from entering the Channel and joining with the Brest fleet. The battle of Trafalgar and its aftermath form the central chapter of the books and Robson writes a lucid and compelling combat narrative without overly dramatising events.

Following Trafalgar, attention turns to the Baltic and the campaigns at Aix Roads and the Scheldt, and thence to the Mediterranean and the war in the Peninsula where Robson highlights the critical role the Navy played in supporting the army; transporting and evacuating troops, carrying specie, and victualing on a grand scale. However the navy were not there just to fetch and carry, they also played an important strategic and tactical role, working in concert with the army to seize and hold important tactical positions.

Leaving the Peninsula, Robson turns his attention to the impact of economic warfare on Britain’s overseas possession in the East and West Indies and at the Cape, demonstrating how trade and commercial interests influenced the war, particularly in the West Indies.

The final two chapters cover the War of 1812 and the Bombardment of Algiers. Robson presents a concise but comprehensive overview of the War of 1812, covering the early American victories, the British blockade of the eastern seaboard, the campaigns on the Great Lakes, culminating in Cockburn’s Washington campaign. By contrast, Robson devotes barely three pages to the Bombardment of Algiers. The political context of this operation is lacking and the engagement itself is presented in only the briefest summary. Unfortunately for a book that admirably balances detail with brevity throughout, this final chapter feels rather tacked on.

Robson concludes by accounting for the cost of the war in terms of men, ships and trade revenues and the figures are staggering. Between 1793 and 1815 British exports increased from £20.4 million to £70.3 million and it was this economic strength, founded on maritime security and protected by the Royal Navy, that crucially enabled Britain to bankroll her continental allies.

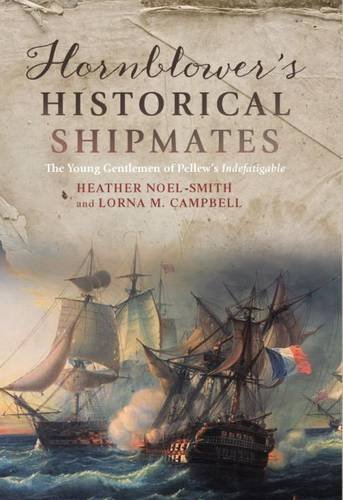

Robson’s addition to the History of the Royal Navy series can be highly recommended both for general readers and for scholars of naval history and the Napoleonic Wars alike. The author provides a concise but comprehensive overview of the Royal Navy’s campaigns during the Napoleonic Wars, and frames the central role played by maritime power in the wider global economic context. As one would expect from I.B. Tauris and The National Museum of the Royal Navy, the production quality of this series is excellent. The Napoleonic Wars is enhanced by numerous illustrations and colour plates and the images of artefacts from the Museum’s collections make a welcome addition to the more familiar portraits, paintings, battle plans and satirical prints.